NEW YORK BLACK FLORIST HISTORY

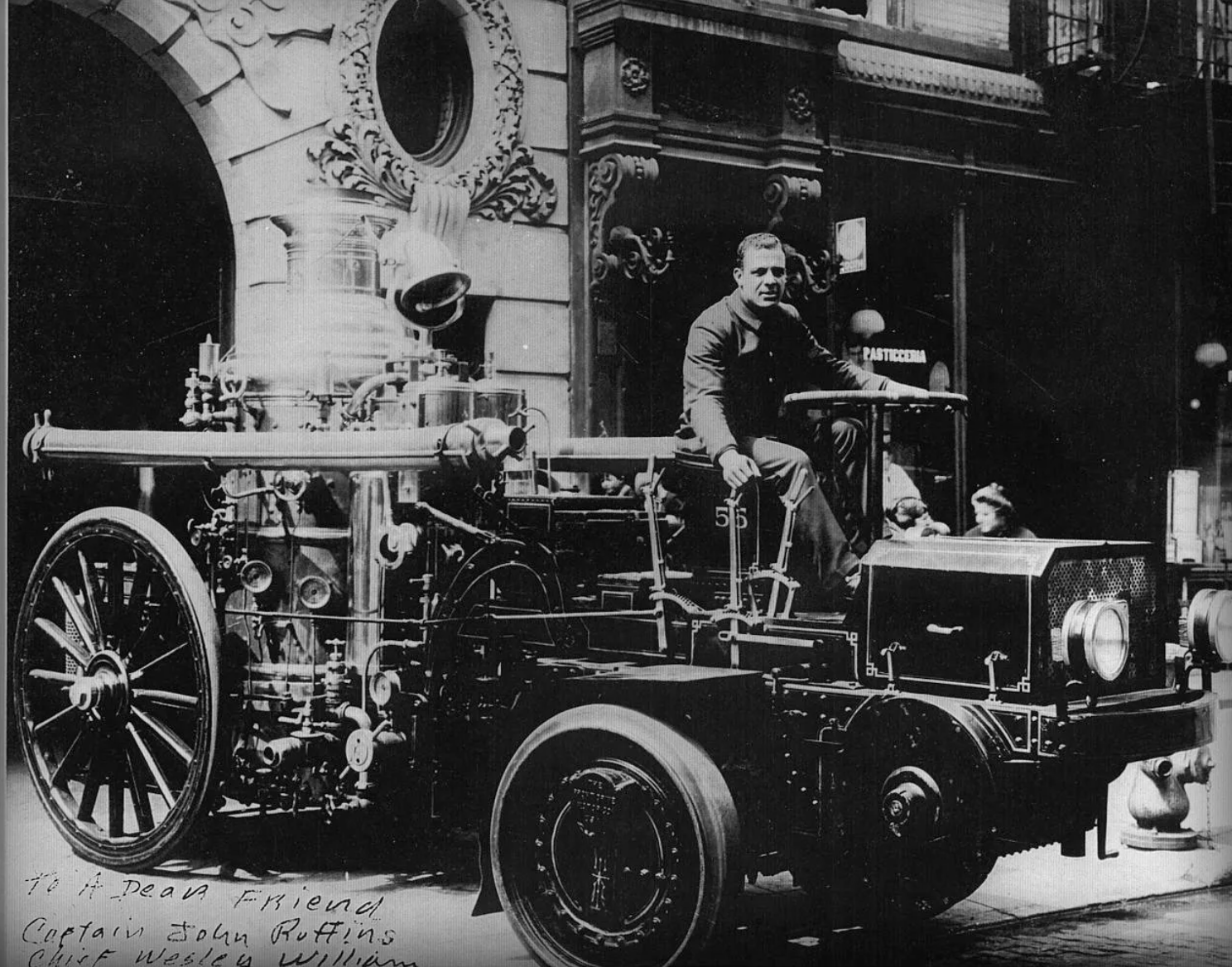

Wesley began working for Charles Thorley in his early teens after school. That experience instilled in him a strong work ethic from a young age. In his later teen years, Wesley took on one of the most physically demanding jobs in New York City—he became a Sandhog, helping to dig the tunnels that would eventually become the city’s subway and underground infrastructure. The grueling labor helped him build immense physical strength.

At the same time, Wesley began strength training and wrestling at the local YMCA, earning him the nickname “The Hercules of Harlem.” He also trained in boxing and wrestling at the Harlem YMCA and could lift over 350 pounds overhead. His discipline and physical power set him apart. Later, he got a job as a mailman, where he learned to drive a truck—an unexpected skill that would prove invaluable later in life.

Wesley’s big break came when he applied to the New York Fire Department. He scored among the top applicants on the entrance exam and needed three letters of recommendation. The first came from his former boss, Charles Thorley, a respected figure known for his contributions to both the NYPD and FDNY. The second came from none other than President Theodore Roosevelt. The third was from financier J.P. Morgan. These endorsements were unprecedented—and controversial.

Many of his Irish-American colleagues in the firehouse didn’t welcome Wesley. He endured relentless harassment: his gear was sabotaged, his helmet repeatedly smashed, his boots filled with rotten chicken and excrement. A wrench was once dropped on his head. He was forced to sleep in the basement and had his utensils damaged. Despite this, he never backed down. Firefighters at the time often settled disputes through bare-knuckle fights in the basement, and Wesley never lost a single one.

One act of bravery stood out. During a major fire, Wesley, by then leading the hose team—faced a sudden backdraft explosion. While the rest of the crew fled in fear, Wesley was knocked down, got back up, and continued battling the blaze until it was out. His courage exposed the cowardice of his tormentors and earned him long-overdue respect.

Because of his earlier experience as a mailman, Wesley was the only one in his company who could drive the fire engine, making him indispensable. Eventually, many of the firefighters who had mistreated him transferred out. Wesley later transferred to a Harlem firehouse, where he made history as the first Black firefighter in FDNY history to be promoted to fire officer.

By the time he retired in 1952, Wesley had risen to the rank of battalion chief. It all started with his first job under Charles Thorley, who—when Wesley was just 11—treated him with dignity and respect. That early experience taught him a powerful lesson: he was valuable, he was equal, and anything was possible.

James Henry William

James Henry Williams's father was tired of him and his two brothers horsing around after school, so they attended the Colored School, located at 81. 128 West 17th Street. He wanted his boys to start working. So he found a listing in the paper and took his brothers to Charles Thorley Florist's shop. James got his first job as a florist messenger when he was nine (1887).

He worked for Thorley until 1923, when he was 45. He also worked as a designer for Thorney and his 2 other brothers. He was a designer as well. The Staff of designers were all black at Thorley Shop, which led to the success of the firm. They provided such beautiful designs and professionalism that hooked the New York “400” influential and wealthy families of the Gilded Age Society to shop only at Thorley’s Shops. After Thorley's death, he moved on to working full-time as a Red Cap. He broke the color line of the profession in 1903.

At the Thorley shop, James first met his wife as a teen. Much later, they got married, and they moved from 318 West 41st Street, Hell’s Kitchen, to the Tenderloin, 228 West 28th Street in the floral district. Many African Americans were invarious kinds of service jobs in the area. Many own their Bars, Clubs, and a few cigar shops.

To be clear, the Floral District was “uptown” in New York at the time and called the Tenderloin. It was called the Tenderloin because it was the area where the poor were harassed by police officers for money. There, the police would get enough money to buy steak for their families.

Greenwich Village was “Little Africa” from 1860 to the 1890s.

James’ Brother John “Wesley” worked for Thorley as well; he’s on the right of James in the photo below.

Langston Hughes

The most notable African American to work for Thorley was Langston Hughes—an acclaimed American poet, social activist, novelist, playwright, and columnist.

Hughes worked as a florist delivery person and assisted in the shop for two years, until Charles Thorley’s passing in 1923.

Herbert D. Cummings

Cummings began his career with Charles Thorley as a designer and clerk, quickly rising to become one of Thorley’s most trusted and valued employees. Recognized for his skill and professionalism, he was assigned to personally oversee the floral needs of Thorley’s most distinguished clientele.

In 1902, when Prince Henry of Prussia became the first European royal to visit the United States, Thorley secured the prestigious contract to provide floral arrangements for the grand gala held in the Prince’s honor at the Waldorf-Astoria. Despite attempts by some to discourage the Prince’s staff from selecting Thorley—citing the diversity of his workforce, the Prince’s team remained firm in their decision. For them, excellence took precedence over prejudice.

Thorley was not only responsible for the elaborate floral decor at the event, but he also entrusted Cummings with a critical and highly visible assignment: maintaining fresh flower arrangements in Prince Henry’s suite throughout his stay. This role proved to be a turning point. The Prince was so impressed by Cummings’ talent and dedication that he appointed him as his personal florist for the duration of his American tour.

Cummings accompanied Prince Henry on a journey that included stops in New York, West Point, Milwaukee, Annapolis, Nashville, and Washington, D.C., where the Prince was introduced to President Theodore Roosevelt. Their professional relationship blossomed into a friendship marked by mutual respect.

Deeply moved by the artistry he experienced, Prince Henry placed an extraordinary order: $6,000 worth of flowers, equivalent to approximately $225,000 today, including 15,000 American Beauty and Winter roses, lilies of the valley, and orchids. The blooms were carefully packed in moss and ice boxes to be shipped back to Germany. As a gesture of gratitude, Thorley gave Cummings $600 (about $22,500 today) to cover his travel expenses while accompanying the royal delegation.

In recognition of his exceptional service, Prince Henry gifted Cummings a luxurious gold watch encrusted with diamonds—a remarkable token of esteem.

During his stay in New York, Prince Henry immersed himself in Black American culture, which had left a lasting impression on him since childhood. At the age of 11, he had witnessed a performance by the Fisk Jubilee Singers during their fundraising tour in Germany to support Fisk University, an institution dedicated to educating formerly enslaved individuals. That experience had moved him deeply and stayed with him into adulthood. Also, all who witnessed the singers were moved to tears.

In New York, the Prince enjoyed performances by the Hampton Singers at the Waldorf-Astoria and Carnegie Hall, where he also had a memorable conversation with Booker T. Washington. Delighted by their exchange, the Prince was thrilled when Washington promised to send him a book of traditional Negro spirituals.

His cultural exploration extended beyond concert halls. He visited a saloon on 53rd Street and the Marshall Hotel, a Black-owned venue, where he was enthralled by the energy of the cabaret scene—filled with vibrant performances of ragtime and popular tunes by Black musicians, singers, and dancers.

In Nashville, the Prince’s historic tour was punctuated by a warm welcome from the renowned Jubilee Singers, closing another chapter of his journey with a powerful reminder of the cultural richness and resilience of African American artistry.

The Fisk Univery Jubilee Singers, when Prince Henry was 11, 1873.

Mr. Cummings & Williams worked on this event at the Waldorf-Astoria. 1902

White House visiting the President 1902, Mr. Cumming had his hand in this.

Prince Henry and the SS Deutschland 1902 First Class Dining Room. This is another area were Mr. Cummings needed to decorate as well during his 5 day trip to Germany from New York.

William Baker

In 1877 he was a floral designer who worked for a florist and in the wholesale market. However, little information is available about him, except that he lived in Hell’s Kitchen at 340 West 49th Street.

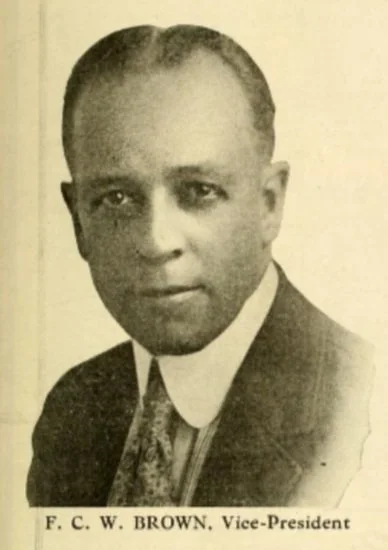

Fredrick C. W. Brown

Fred C. W. Brown served as the Vice President of the Society of American Florists & Ornamental Horticulturists. Throughout his career, he traveled extensively, delivering lectures on floral design and showcasing his remarkable arrangements. Born in 1875, the last known mention of his work dates back to the 1940s. Below is an arrangement attributed to him that I discovered.

Joel Cooley

Mr. Cooley lived and worked on his family’s oyster beds off Staten Island until 1912. His family, among the first freed oystermen from Gloucester, Virginia, migrated to Tottenville, Staten Island, in 1870. This was the thinking back then, “If you were a farm laborer, you would have made $10 a week. So, if you were a meat packer, you might have made $25 a week. But if you were a waterman, you could make $100 a day,” Holmes-Turner says, describing why so many Rushmere men turned to the water. So Cooley’s family prospered for 40 years. However, in 1912, due to pollution in the surrounding waters, New York City authorities condemned oyster harvesting. At 48 years old, Mr. Cooley retired, using his savings to pursue a new passion—growing dahlias.

A key to his success was incorporating crushed oyster shells into the soil, which enriched it and contributed to the remarkable growth of his flowers. His thriving garden quickly gained local fame, becoming a point of admiration throughout the area. Mr. Cooley soon joined the Staten Island Horticultural Society, making history as the first person of color to become a member. His exceptional blooms earned him numerous awards, and he went on to exhibit and win GOLD & Silver medals at the prestigious Madison Square Garden flower shows.

1912 Gold medal for The Best Dahlias in a Basket, Silver for Best Display, and Bronze for Best Varieties in the Staten Island Staten Hort Society 6th Annual Dahlias show at the Public Museum of Arts & Science.

In addition to his achievements with dahlias, Mr. Cooley was also a pioneer in cultivating and commercializing figs on Staten Island. Dahlia enthusiasts from far and wide visited to witness his extraordinary blooms firsthand. Passed away in 1932 at 67 years old.

Yes, shucking oysters provided good money, but it was grueling, demanding work.

LUCILLIE CAINS

HOUSE OF FLOWERS

Above: She won first prize for “Originality” a hat of 35 Hawaiian orchids and baby flowers at the show at the Metropolitan Retail Florist Show. She was the only Afro-American florist exhibiting at the show. This took a lot of courage in New York in 1954. She got her flowers from Thomas Young Orchid Grower in the Floral District. She was 56 at the time. Amazingly beautiful woman.

She supplied Billie Holiday with gardenias. Her store closed in 2011.

Lucille married into the business in 1918, 2306 Seventh Avenue, Harlem. Over those years she was devoted to the floral district all those years. She was born in 1898.

Benjamin Franklin Butler Jr.

BUTLER’S FLOWERS

Benjamin Franklin Butler established the first Black-owned florist shop in Brooklyn in 1919 at 1710 Fulton Street, Brooklyn. Records show that, at the age of 17, he was a florist helper. At 22, he was newly married, and he and his wife resided in the apartment above the shop. The business served the community for over 40 years before closing its doors in 1963 when he passed away. He took part in local politics and served his community.

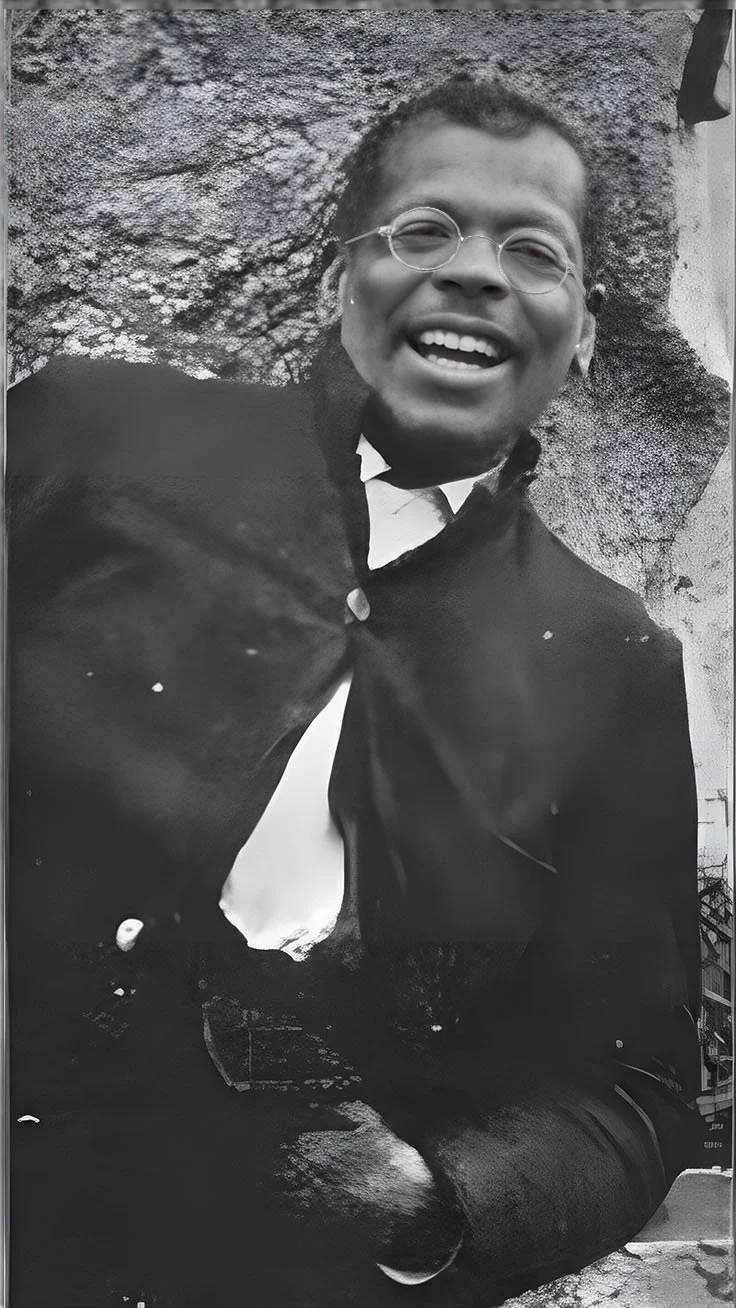

Anthony Riley

Like many African Americans during the Civil War, Andy found a new purpose and a fresh start after escaping slavery in the South. Enslaved since childhood on General Robert E. Lee’s plantation in Virginia, he spent his early years in servitude. In his twenties, while in a Confederate war encampment, he seized an opportunity to flee, seeking freedom with Union troops.

Although Andy was never part of New York’s florist community, he played a significant role in the broader floral and horticultural world. He eventually secured work at Horticultural Hall in Boston, where he dedicated 40 years to maintaining the grounds with care and enthusiasm. His unwavering dedication and warm spirit earned him the affectionate title of "Mayor" of the institution. In the photo to the left, he is in his sixties, a testament to a life of resilience and purpose.

More to come…..